How circadian rhythm, melatonin, and evening habits quietly shape your midlife hormones

The Rhythm Behind the Hormones

In Part 1, we explored a truth that often surprises women: women’s health does not begin in the ovaries. It begins much earlier — in the brain.

When we talk about a woman’s hormonal health, the ovaries are rarely the root cause of her symptoms.

A woman’s wellbeing depends on the balance of all glands — and, above all, on whether the brain feels safe and in rhythm.

One of the biggest disruptors to hormonal harmony is not “ovarian decline,” but a brain that perceives danger — sometimes constantly. And in today’s world, most women live in that state without even realizing it.

Artificial light long after sunset. Irregular meals. Chronic stress we carry without noticing. Overstimulation, emotional strain, unresolved trauma.

Even a late-night thriller or blockbuster can activate stress pathways, because the brain responds biologically, not logically.

And then there is the inner clock — the circadian rhythm that sets the tempo for every hormone.

When this clock is disrupted, the entire network shifts: the stress axis, metabolism, thyroid, pancreas, and reproductive rhythm all begin to drift out of sync.

This is why so many modern symptoms blamed on the ovaries — fatigue, mood changes, missed periods, weight gain, PMS — often originate much earlier in the system, long before ovarian function truly declines.

But this isn’t a failure — it’s your body trying to communicate, long before anything truly goes wrong.

When we bring our lifestyle closer to our natural rhythms…

When we understand how the female body actually works…

When we create safety again — through nourishment, rest, and rhythm…

…the entire system softens. And a sense of trust in your own body grows.

This chapter is about exactly that: practical lifestyle shifts that relieve the system, restore hormonal rhythm, and help you feel balanced again — not perfectly, but in harmony with your biology.

Hormonal balance doesn’t begin in the ovaries. It begins in the brain.

And to bring that rhythm back, we work from the top down and the inside out —supporting the hypothalamus, the pineal gland, the thyroid, the pancreas, and finally the ovarian connection.

This chapter isn’t a protocol — it’s a rhythm. A way of living that helps your brain and body find alignment again, and regain their sense of safety.

Let’s begin.

The Long-Term Cost of “Normal” Modern Habits

Before we talk about restoring your body’s natural circadian rhythm, it helps to see how effortlessly modern life can push it off course.

Let’s imagine the evening routine of a typical modern woman.

After a long day, she finally sits down to unwind — scrolling through Instagram, finishing a few emails, watching a show to relax. The room is bright, the screen even brighter.

Dinner might be late— pasta, steak, maybe dessert — washed down with a glass of wine to take the edge off. And because she feels she “deserves” some time for herself, bedtime drifts later and later.

Midnight doesn’t feel late anymore. But for her biology, it is.

She falls asleep exhausted, not naturally.

She wakes to a loud alarm, not to sunlight.

She reaches for coffee before she’s even fully conscious, because without it, her body doesn’t seem to start.

Nothing about this looks unusual.

In fact, it looks normal — the modern woman’s life.

But her biology doesn’t see “normal.”

Her biology sees signals.

Light at night tells the brain: It’s still daytime.

A heavy dinner tells the pancreas: Work overtime.

Alcohol tells the pineal gland: Slow down melatonin production.

Stress and late-night stimulation tell the hypothalamus: Danger.

And melatonin — the molecule women underestimate the most — quietly disappears.

Melatonin: More Than a Sleep Molecule

Melatonin is not “just a sleep hormone.”

Emerging research suggests it may play a role in:

- mitochondrial protection (one of the strongest endogenous antioxidants)

- thyroid rhythm regulation

- cortisol balancing

- insulin sensitivity and appetite hormones

- ovarian aging and follicular protection

- estrogen and progesterone receptor modulation. [3, 8, 10–12, 17, 23–25]

When melatonin stays chronically low, women may experience:

- lighter, fragmented sleep

- more PMS fluctuations

- irregular cycles

- stronger evening anxiety

- increased insulin resistance

- slowed thyroid function

- more pronounced perimenopausal symptoms

- faster visible aging. [3, 5, 10–12, 17, 23–25]

Some researchers even suggest that long-term nighttime light exposure — through melatonin suppression— may be associated with increased breast cancer risk. Not as a claim, but as a growing area of scientific interest. [13, 14, 20, 21]

And when you look at all these downstream effects, it becomes clear why supporting your circadian rhythm is so important in midlife.

When nighttime signaling is disrupted not once, but every night… not for a season, but for years… the body’s rhythm begins to soften and drift.

- Within a few years, sleep often becomes lighter, PMS more pronounced, energy flatter.

- Over a decade, insulin resistance may creep in, recovery slows, skin loses brightness.

- As the years continue, cycles can become irregular, mood more fragile, weight harder to regulate.

- And after long-term disruption, symptoms that resemble early menopause may appear long before ovarian function truly declines. Ovarian symptoms are often the last step in a long chain of disrupted signals. [3, 5, 17, 20, 22–25]

And this is the quiet price we pay for habits that feel so normal. When the cues never arrive, the body simply can’t produce melatonin on time.

Some women might think: “If melatonin is so important, maybe I should just supplement it.”

And for some —especially women over 60 or individuals with specific medical conditions — melatonin support may be appropriate under medical guidance.

But for many women under 60, disrupted sleep is not a melatonin deficiency.

It is an environmental signal problem — the result of a lifestyle that no longer aligns with the body’s internal clock.

And no supplement can compensate for chronically mistimed signals or replace the daily rhythms that support healthy hormone communication and slower biological aging.

Before considering long-term supplementation, it’s worth looking at the true disruptors:

artificial light, alcohol, caffeine, emotional hyperactivation, irregular meals, and the chronic “always-on” state of modern life.

Let’s break these modern habits down.

How Modern Habits Disrupt Melatonin

Melatonin is extraordinarily sensitive. It doesn’t respond to logic — it responds to signals.

- Bluelight (screens, LEDs): Some studies suggest it can suppress melatonin by 50–80% within minutes, telling the brain it’s still daytime. [1, 2, 20]

- Late or heavy meals: Trigger insulin and digestion, which suppress melatonin synthesis and keep the body in “day physiology.” [17, 23–25]

- Alcohol: Even a single glass may blunt melatonin release and fragment deep sleep phases. Alcohol tends to reduce deep sleep and fragment the night. Studies suggest that even moderate evening drinking may reduce deep sleep in some individuals. [18]

- Caffeine in the afternoon or evening: Delays DLMO (dim-light melatonin onset) and shifts circadian timing forward. In clinical studies, caffeine reaches its peak effect after about 40 minutes — but its biological half-life is much longer (around 5–9 hours). Even a 3 p.m. coffee may still be active at 10 p.m.–midnight, delaying melatonin onset and reducing deep sleep, even if you fall asleep easily. [19, 25]

- Emotional activation or stress: Cortisol and melatonin work in opposite directions — when cortisol rises, melatonin naturally falls. [15, 16, 25]

If these habits sound familiar, you may also recognize the sensations they create — lighter sleep, waking unrefreshed, feeling “switched on” even at night. And now you can see the reason behind it: your brain has been receiving signals that keep it in day mode, even when you’re trying to rest. Once you understand that, the symptoms finally make sense — and so does the path back to balance.

Before we can restore hormonal balance, it helps to understand how your body’s timing system actually works — and how quietly it can slip out of sync.

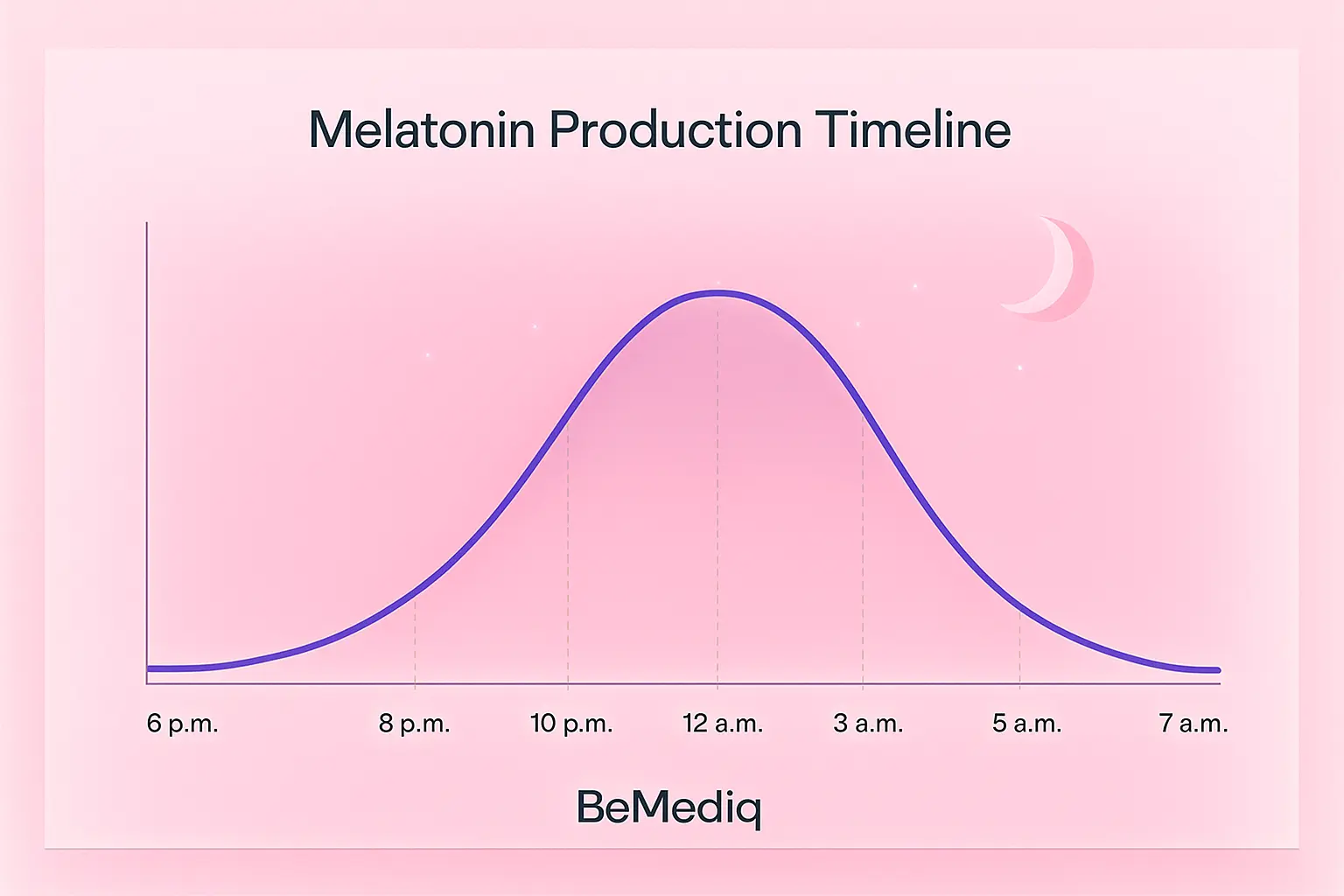

The Melatonin Production Timeline

Values represent general patterns, not exact percentages, and may vary among individuals.

- DLMO (Dim Light Melatonin Onset): ~ 6:00–8:00 p.m. This is when the system begins switching into night mode. DLMO determines the moment your brain starts producing melatonin — and this timing can shift hours earlier or later depending on your evening habits, light exposure, and emotional state.

- Rise: ~ 9:00–10:30 p.m. Melatonin increases steadily, core temperature falls, and the body prepares for repair. This is also the ideal window to fall asleep, so the first deep-sleep cycle can begin on time — the phase most responsible for recovery, repair, and hormonal stability.

- Peak :~ 12:00–3:00 a.m. This is the repair window: mitochondrial recovery, antioxidant defense, and the activation of the glymphatic system — the brain’s nighttime cleansing mechanism that clears metabolic waste and supports cognitive health. A crucial detail for anyone who relies on high cognitive performance: this process is foundational for clarity, memory, and next-day mental sharpness.

- Decline: ~ 3:00–5:00 a.m. Melatonin gradually falls as the brain prepares to wake. For many people, this is the biologically easiest time to wake without grogginess — the transition phase between night physiology and morning readiness.

- Off:~ 6:00–7:00 a.m. Morning light — especially natural daylight — shuts down melatonin almost entirely and resets the circadian clock for the next 24 hours.

The way our inner clock responds to light makes one thing unmistakable: deep sleep doesn’t simply appear at midnight — it’s built over the hours that lead into the night. The evening routine is the quiet runway that prepares the body for hormonal balance. [3, 8, 22, 23, 25]

And what happens when sleep begins at midnight? According to circadian researchers…

- Sleeping at 00:00 is often associated with a markedly reduced melatonin peak — in some studies, a loss of roughly 40–60% of normal nightly output. [1, 2, 19, 25]

- Sleeping at 01:00 or later may lead to an even more substantial reduction in melatonin production, with estimates of up to 70–90% on certain nights. [1, 2, 19, 25]

What does the science teach us? Melatonin does not wait for you. Just like an orchestra, the rhythm begins on time — and it will not replay the opening because you arrived late.

This also explains why late bedtimes rarely “shift the night forward.” The melatonin peak is driven by your internal clock, not by the moment you fall asleep — which means that when sleep begins at midnight, much of the peak repair window is already underway, and the remaining portion is often cut short by morning light.

Based on what we know from circadian physiology, many experts consider a roughly 10 p.m.–6 a.m. sleep window to be most in harmony with natural melatonin timing.

To understand how crucial the day–night rhythm is for mental health, performance, youthfulness,and longevity, it helps to compare two very different melatonin profiles: that of a young adult — and that of a 60-year-old.

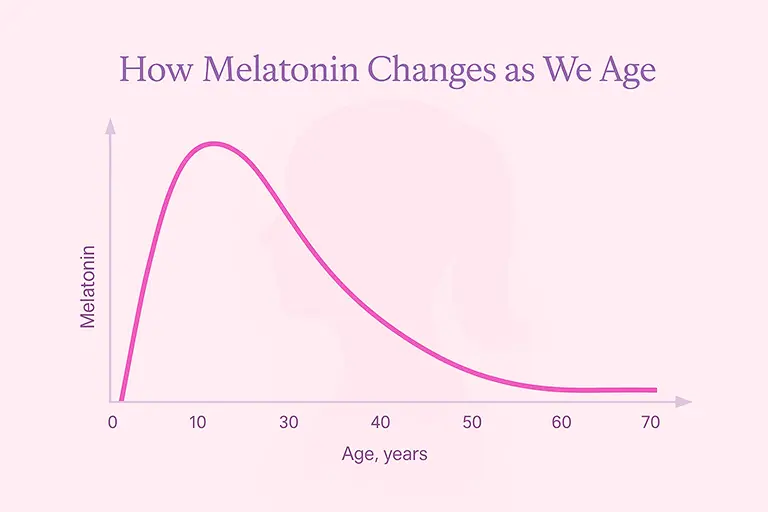

How Melatonin Changes as We Age

Melatonin naturally declines with age — a finding consistently reported in circadian and endocrine research over the past decades. By our 50s and 60s, the pineal gland produces far less than it did in our twenties, which is one reason why sleep becomes lighter and recovery slower in midlife. [3, 5, 9, 12]

But here is the part most women are never told:

Modern life can push this decline decades earlier.

Chronic evening light, late meals, alcohol, stress, and overstimulation can suppress melatonin so consistently that many women in their 30s or 40s operate with melatonin levels similar to those seen much later in life.

This is why some women in their late thirties or early forties feel far older than they are.

Not because their body is irreversibly aging, but because it never receives the biological signals required to produce melatonin in the first place.

When this continues year after year, the consequences accumulate — the very symptoms we discussed earlier: lighter sleep, stronger PMS, higher nighttime anxiety, blood-sugar instability, weight changes, and more.

This premature melatonin aging is one of the silent drivers behind symptoms often blamed on perimenopause — long before ovarian function truly begins to shift. [10–12, 17, 23–25]

But here is the hopeful truth: unlike natural aging, lifestyle-driven melatonin suppression is at least partially reversible.

The moment the brain receives the right cues — real darkness at night, real daylight in the morning, regular meals, calmer evenings — melatonin often begins to rebound.

This is where rhythm becomes medicine — and where lifestyle becomes one of the most powerful hormonal tools a woman has. [17, 22–25]

Hormonal harmony begins with the body’s timing system — the circadian rhythm.

Once we understand how easily the rhythm is disrupted — and how deeply it influences thyroid function, blood sugar stability, stress regulation, and even ovarian feedback —the next step becomes clear:

Hormonal harmony begins with the body’s timing system — the circadian rhythm. Restoring that inner clock is the first step.

Lifehacks: How Evening Habits Shape Melatonin — and Your Hormonal Rhythm

Melatonin is far more than a “sleep hormone.” It is a circadian signal, a metabolic regulator, and one of the body’s strongest endogenous antioxidants — especially inside the mitochondria, the tiny energy centers where melatonin shields cells from oxidative wear and helps them stay energized and youthful. But melatonin is also extremely sensitive. The hours before bedtime can either amplify it… or quietly silence it.

Most modern evenings follow a familiar pattern: bright screens, late dinners, emails, dopamine hits from scrolling, a glass of wine to relax, and finally collapsing into bed close to midnight. It feels normal — even deserved.

But to restore rhythm, it helps to imagine a different kind of evening — one that works with a woman’s biology instead of against it.

The Rhythm-Revering Evening — A Story to Anchor the Body’s Natural Cues

After a long day, she comes home just after sunset and slips on warm-toned blue-light-blocking glasses — not as a rule, but as a quiet signal to her brain that the day is softening. Her home glows with warm, cozy lamps under 2,700 K, the kind of light that allows the pineal gland to sense that night is near.

Dinner is simple, satisfying, and light on the system: a vegetable soup, a zucchini stew, or a lentil curry she prepped earlier in the week. No heavy sauces, fried foods, or sugary desserts — those belonged to the afternoon, where her cacao and carrot muffin felt grounding, not disruptive.

Her caffeine window closed hours ago; she keeps it before noon, knowing how strongly it shifts her internal clock.

She also skips the evening wine — not out of restriction, but out of awareness. She knows even one glass can fragment deep sleep and alter its architecture, sometimes mimicking the sleep pattern of someone much older.

Instead, she pours a golden milk or herbal tea and lets it warm her whole system.

Rather than intense exercise, late-night messages, or emotional thrillers that spike cortisol, she chooses gentle movement — a walk, stretching, or 4-7-8 breathing that sends a message her brain has been waiting for:

You are safe. The day is done.

If she wants entertainment, she chooses something uplifting, humorous, or soothing. Not horror, dramatic news, or doomscrolling — because her hypothalamus cannot distinguish fictional danger from real threat.

By the time she begins her evening ritual — warm bath, skincare, soft music, gratitude — her body has already been preparing for hours.

Falling asleep is no longer a collapse. It’s a gentle, supported landing.

1. Block the Blue Light: The Fastest Melatonin Disruptor

We can influence one of the strongest melatonin blockers with simple, stylish habits — without sacrificing quality of life.

Supportive shifts:

- Use blue-light-blocking glasses (orange/amber lenses) in the evening, especially with screens.

- Create a “digital sunset”: reduce or stop bright screen use 2–3 hours before bed when possible.

- Switch to warm, low-light lamps (around < 2,700 K) instead of bright white overhead lighting.

- Activate night mode and reduce screen brightness in the evening.

If evening screentime is unavoidable, combining blue-blocking glasses + warm ambient light + low brightness can significantly reduce the impact.

2. Avoiding Late or Heavy Meals (When Insulin Blocks Melatonin)

You don’t need to fast in the evening — simply re-timing and lightening dinner already helps. Insulin directly suppresses AANAT — a key enzyme required for melatonin synthesis.

Heavy evening meals keep the body in “day mode” by raising insulin, body temperature, and metabolic activity.

How late is too late?

Ideally, finish dinner 2.5–3 hours before bedtime, and not later than about 8 p.m.

What counts as “heavy”?

- very large portions

- high-fat, rich meals (pizza, fried foods, creamy sauces)

- high-starch meals without fiber or protein

- red meats

- desserts or sweet snacks close to bedtime

Gentler evening options after about 6–7 p.m.:

- vegetable soups

- steamed or roasted vegetables

- light protein portions (e.g. lentils, yogurt, tofu, fish depending on diet)

- small portions of whole grains (quinoa, buckwheat, amaranth) with fiber, not as plain starch

This doesn’t mean restriction — it means re-timing density: more substantial meals earlier, lighter meals as the body prepares for night physiology.

3. No Alcohol in the Evening

Alcohol tends to reduce deep sleep and fragment the night. Studies suggest that even moderate evening drinking may reduce deep sleep in some individuals.

Rough metabolism guideline:

Alcohol is broken down at around 0.1–0.15‰ per hour.

A standard glass of wine (~0.3–0.4‰) often requires 3–4 hours to clear.

If consumed at all:

- aim to have the last drink at least 4 hours before bedtime

- avoid combining alcohol with very late meals

Supportive swaps:

- herbal teas (e.g. chamomile, lemon balm, rooibos)

- warm water with citrus or ginger

- golden milk (e.g. turmeric with plant milk)

- alcohol-free alternatives reserved for earlier in the evening

4. No Caffeine After 12 p.m.

That comforting 3 p.m. cappuccino? Caffeine blocks the adenosine receptors that normally tell your brain, “It’s time to slow down.” Because caffeine can linger for 5–9 hours, it may still be active at 10 p.m.–midnight — the window when melatonin needs to rise. Your body is already in bed, but your brain hasn’t received the signal that night has begun.

Practical rule of thumb: No caffeine after 12:00–14:00, depending on sensitivity.

Supportive alternatives later in the day:

- cacao (naturally lower in caffeine and rich in magnesium)

- rooibos or herbal teas

- chicory-based “coffee” drinks

- goldenmilk or warm plant milk with spices

5. Teach the Brain That the Day Is Over

Melatonin and cortisol are biological opposites. Anything that raises cortisol can suppress melatonin for 30–90 minutes — even if the “threat” is only on a screen.

For the brain, an emotional thriller, late-night argument, or stressful email can be interpreted as real danger.

Typical evening triggers:

- horror, action, or very intense films/series

- emotionally charged conversations

- doom scrolling and news consumption

- mentally demanding work late at night

- revisiting unresolved worries just before bed

Nervous-system cool-down options:

- 4-7-8 breathing (or similar breathwork) to activate the vagus nerve in under 90seconds

- a warm shower or bath to relax muscles and lower tension

- journaling or a “brain dump” to clear mental loops

- 10–15 minutes of gentle walking, ideally outside

- Yin yoga or stretching as a daily closing ritual

- a weighted blanket or grounding practices for those who find them soothing

These are not “wellness extras” — they are practical tools to teach the brain that the day is truly over and it is safe to let go.

6. Intense Evening Exercise

Movement is essential for metabolic and hormonal health — but timing matters. Intense exercise in the late evening can:

- increase cortisol and adrenaline

- raise core body temperature

- delay the natural melatonin rise

Best timing: finish vigorous training by around 6:00–6:30 p.m. whenever possible.

After 6:30 p. m., choose:

- relaxed walking (even a short after-dinner walk supports glucose regulation)

- gentle stretching

- restorative or Yin yoga

A simple evening walk can do more than you think: it steadies blood sugar, helps your digestion wind down, and brings the nervous system into a calmer rhythm — all without raising stress hormones.

In essence:

The simplest way to stabilize the hypothalamus and pineal gland is not a pill — it is light, timing, and emotional safety.

- Morning sunlight within the first hour after waking acts as a biological reset button.

- Calmer, darker evenings open the door for melatonin to rise.

- And consistent, nourishing meals give the brain the message it listens for most:

You are safe. You can rest. You don’t have to be on alert all the time.

The first step is bringing your circadian rhythm back into balance — the internal timing system your hormones rely on. Once that foundation is in place, supporting the thyroid, steadying blood sugar, and supporting the hormonal signaling that connects the brain and the ovaries becomes far more effective.

In Part 3, we explore how daytime habits shape the entire hormonal network.

Key Takeaways — Part 2: The Hidden Cost of Modern Evenings

1. Hormonal balance begins in the brain — not in the ovaries.

The hypothalamus, pineal gland, and circadian rhythm set the foundation for hormonal harmony long before ovarian changes occur.

2. Melatonin is far more than a sleep hormone.

It is a circadian signal, a metabolic regulator, and a powerful mitochondrial antioxidant that shapes energy, stress, blood sugar, and reproductive health.

3. Modern evening habits can suppress melatonin for years before ovarian function shifts.

Late meals, bright light, screens, alcohol, and emotional overstimulation are major disruptors.

4. Lifestyle-driven melatonin suppression can mimic early perimenopause.

Lighter sleep, PMS changes, mood fragility, blood-sugar swings, and morning fatigue often reflect mistimed signals — not ovarian decline.

5. Melatonin needs darkness and timing — not willpower.

It rises only when light, insulin, caffeine, and cortisol fall at the right time. You cannot “force” it to appear once the window has passed.

6. A 3 p.m. coffee can still be active at 10 p.m.–midnight.

By blocking adenosine receptors for 5–9 hours, caffeine can delay melatonin onset even if you go to bed on time.

7. Sleeping at midnight compresses the melatonin peak.

The body enters deep sleep later and loses 1–3 hours of repair time — which often feels like unexplained exhaustion the next day.

8. Circadian misalignment builds slowly — layer by layer.

9. Rhythm first — hormones second.

A restored circadian rhythm makes thyroid function, blood-sugar stability, and brain–ovary signaling far more responsive.

10. The evening routine is hormonal self-care.

Warm light, earlier dinners, fewer stimuli, no alcohol, and calming rituals give the brain the signals it needs to produce melatonin and repair the body overnight.

FAQs — Part 2: Circadian Rhythm, Melatonin & Modern Evenings

1. Why do modern evening habits affect my hormones so strongly?

Because light, food, caffeine, alcohol, and emotional stimulation all send timing signals to the hypothalamus. When these signals arrive at the wrong time — especially in the evening — they suppress melatonin and shift the entire hormonal rhythm downstream.

2. If melatoninis so important, why not just take a melatonin supplement?

Supplemental melatonin can help in specific cases (age 60+, jet lag, certain medical indications), but for most women under 60, low melatonin is not a deficiency —it’s a signal problem. No supplement can override bright light, late meals, caffeine, or stress pathways that tell the brain “it’s still daytime.”

3. How long does it take to restore a healthy circadian rhythm?

Most women feel improvements within 7–14 days of consistent evening habits (lighter dinners, darker evenings, earlier wind-down). Deep benefits — sleep quality, mood, PMS patterns, energy — may take several weeks to months, depending on how long the rhythm was disrupted.

4. Does one late night or one glass of wine ruin my melatonin?

Not at all. Hormones respond to patterns, not perfection. Occasional late nights or wine are not the issue — the problem is when modern evening patterns become the norm.

5. Why does caffeine in the afternoon affect sleep at night?

Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors — the receptors that normally build sleep pressure during the day. With a half-life of 5–9 hours, a 3 p.m. coffee may still beactive at 10 p.m.–midnight, delaying melatonin onset and shortening deep sleep.

6. Can evening exercise affect melatonin?

Intense workouts raise cortisol, adrenaline, and body temperature — all of which suppress melatonin. A rule of thumb:

vigorous exercise before 6 p.m. is generally fine; after that, gentler movement (walking, stretching) supports the circadian shift.

7. What is the glymphatic system, and why does it matter?

The glymphatic systemis the brain’s nighttime cleansing mechanism. It becomes active during deep sleep, clearing metabolic waste and supporting next-day clarity, mood, and cognitive performance.

If melatonin rises late or deep sleep is shortened, this cleansing window becomes compressed.

8. Why do symptoms like PMS, mood changes, and fatigue improve when sleep rhythm improves?

Because melatonin regulates multiple systems: stress axis, blood sugar, thyroid timing, brain–ovary communication, inflammation. When the circadian rhythm is back in sync, these systems “work together” again instead of competing.

9. Is it normal to feel tired earlier when I fix my evening routine?

Yes — and it’s a good sign. It means your circadian rhythm is shifting back to its natural timing, and melatonin is rising when it should.

10. What is themost important change I can start with?

Warm light and anearlier dinner are the most impactful changes. If you want to take it one stepfurther, try blue-light–blocking glasses and limit screens in the last 1–2hours before bedtime — this helps melatonin rise naturally and makes fallingasleep easier.

Disclaimer: These statements are for informational purposes only and have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This content is not intended to diagnose,treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider before starting any supplement or therapy.

About this article: This is an evidence-informed educational piece. It draws on peer-reviewed research to explain complex physiology in accessible language, but it is not itself a peer-reviewed scientific paper.

Written by Elena Brull, FNR, Functional Nutrition Researcher & Women’s Health Journalist

About the Author

Elena Brull, FNR, is a Functional Nutrition Researcher and Women’s Health Journalist specializing in integrative approaches to hormonal balance, nutrition, and longevity. Her work combines evidence-based insights with holistic health principles to help women understand their biology and live in rhythm with it. She writes from a non-clinical, educational perspective — with the intention to inform and empower, not to diagnose or prescribe.

Citation:

Brull, Elena. Why the Brain Dominates Perimenopause – Part 2. BeMediq Scientific Spotlight, November 2025. Available at: https://www.bemediq.com/blogs/why-the-brain-dominates-perimenopause-part-2

References

1. GooleyJJ, Chamberlain K, Smith KA, et al. Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses melatonin onset and shortens melatonin duration in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E463-E472. PMCID: PMC3047226 PMID: 21193540, , DOI: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-2098

2. Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness, PNAS. 2015; 112(4):1232–1237. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015 Jan 27;112(4):1232-7. PMID: 25535358, PMCID: PMC4313820, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1418490112

3. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Galano A. Melatonin: a multitasking molecule. Prog Brain Res. 2010:181:127-51. PMID: 20478436 DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81008-4.

4. ZhdanovaI V. Melatonin as a hypnotic: Pro. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9(1):41-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2004.04.003,

5. Karasek M. Melatonin, human aging, and age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2004 Nov-Dec;39(11-12):1723-9. PMID: 15582288, DOI: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.04.012.

6. Hardeland R. Melatonin and the pathologies of weakened or dysregulated circadian oscillators, J Pineal Res. 2017 Jan;62(1). PMID: 27763686, DOI: 10.1111/jpi.12377.

7. Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, de la Torre-Hernandez JM, et al. Melatonin and circadian biology in human cardiovascular disease J Pineal Res. 2014;57(1):14–25. PMID: 20536686, DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00773.x.

8. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Osuna C, Gitto E. Actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress: a review. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7 (6):444–458. PMID: 11060493, DOI: 10.1007/BF02253360.

9. Reiter RJ. The melatonin rhythm: both a clock and a calendar. Experientia. 1993 Aug 15;49(8):654-64. PMID: 8395408, DOI: 10.1007/BF01923947.

10. Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Terron MP, et al. Melatonin and the ovary: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Fertil Steril. 2009 Jul;92(1):328-43. PMID: 18804205, DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.016

11. Basini G, Grasselli F. Role of Melatonin in Ovarian Function. Animals (Basel). 2024;14(4):644. PMID: 38396612. PMCID: PMC10885985.

12. Greendale GA, Witt-Enderby P, Karlamangla AS, Munmun F, Crawford S, Huang M, Santoro N. Melatonin Patterns and Levels During the Human Menstrual Cycle and After Menopause. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(11):bvaa115. DOI:10.1210/jendso/bvaa115. PMID: 33094207. PMCID: PMC7566378.

13. Sánchez-Barceló EJ, Cos S, Mediavilla D, Martínez-Campa C, González A, Alonso-González C. Melatonin–estrogen interactions in breast cancer. J Pineal Res. 2005;38(4):217–222. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00207.x. PMID: 15813897.

14. Cos S, González A, Martínez-Campa C, Mediavilla MD, Alonso-González C, Sánchez-Barceló EJ. Melatonin as a selective estrogen enzyme modulator. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8(8):691–702. DOI: 10.2174/156800908786733469. PMID: 19075592.

15. Rivier C, Rivest S. Effect of stress on the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis: peripheral and central mechanisms. Biol Reprod. 1991;45(4):523–532. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod45.4.523. PMID: 1661182.

16. Viau V. Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal and –adrenal axes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14(6):506–513. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00798.x. PMID: 12047726.

17. Cipolla-Neto J, Amaral FG, Afeche SC, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin, energy metabolism, and obesity: a review. J Pineal Res. 2014;56(4):371–381. DOI:10.1111/jpi.12137. PMID: 24654916.

18. Roehrs T, Roth T. Sleep, sleepiness, and alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(2):101–109. PMID: 11584549. PMCID: PMC6707127.

19. Burke TM, Markwald RR, McHill AW, Chinoy ED, Snider JA, Bessman SC, Jung CM, O'Neill JS, Wright KP Jr. Effects of caffeine on the human circadian clock in vivo and in vitro. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(305):305ra146.v DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5125. PMID: 26378246. PMCID: PMC4657156.

20. Haus EL, Smolensky MH. Shift work and cancer risk: potential mechanistic roles of circadian disruption, light at night, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(4):273–284. DOI:10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.003. PMID: 23137527.

21. Stevens RG. Electric light causes cancer?: Surely you're joking, Mr. Stevens. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2009;682(1):1–6. DOI:10.1016/j.mrrev.2009.01.003.

22. Albrecht U. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron.2012;74(2):246-260. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.019 PMID: 22542179

23. Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science.2010;330(6009):1349-1354. PMID: 21127246, PMCID: PMC3756146, DOI: 10.1126/science.1195027

24. Engin A. Misalignment of Circadian Rhythms in Diet-Induced Obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024;1460:27–71. DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-63657-8_2. PMID: 39287848.

25. Huang W, Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Bass J. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2133–2141. DOI:10.1172/JCI46043. PMID: 21633182. PMCID: PMC3104765.

License:

© 2025 BeMediq.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Educational sharing is permitted; commercial use or modification requires written permission from the author and BeMediq.

This article also appears in the BeMediq Scientific Spotlight collection, archived on Zenodo (DOI pending).